Imagine having an opportunity to travel all around the globe and do the job that you love – cover the events of the world’s magnitude with your camera. And now imagine that those events are wars and international conflicts. And then imagine being held captive for just doing your job in the wrong place at the wrong time.

This is a journey of a three-time Pulitzer Prize and Emmy award-winning photojournalist and phenomenal human being – Barbara Davidson.

We got a chance to have a very open and honest conversation with Barbara on what it takes to capture complex stories and tell them to the entire world, on how to survive the aftermath of constantly witnessing horrific events, how true journalism still matters, and in what way NFTs are reshaping photography and the artistic world.

Barbara is a photojournalist, artist, and creator with 20 years of experience. She has worked at the Dallas Morning News, the Washington Times, and the Los Angeles Times. She has covered the aftermath of Chernobyl in Ukraine, international wars in Bosnia and Israel, the war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the consequences of gang violence in Los Angeles.

Here’s my conversation with Barbara Davidson:

Your project, Caught in the Crossfire: Victims of Gang Violence (which received the 2011 Pulitzer award in Feature Photography and the 2011 Emmy Award for New Approaches to News and Documentary Programming), tells a story about victims and survivors of the gun violence on the streets of Los Angeles. After years of covering international affairs and conflicts, how did you come to a decision to cover something so close to home?

I was working at the Dallas Morning News, and I was traveling all over the world, covering military conflicts in Israel, the war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan, and conflicts in Somalia.

I was traveling a lot telling these kinds of stories, and then the Los Angeles Times noticed my work and decided to offer me a job. I understood that I would not be traveling as much because they already had the team in place for that. And honestly, I was grateful for that because it meant that I could have a normal life, that I won’t have to travel six months out of the year.

After getting hired here, I started to see situations where people were getting shot. And there were no consequences. And it kept on happening. So I thought to myself, “this is very strange,” especially for me – I’m a Canadian, and I didn’t grow up with this kind of violence.

“Caught in the Crossfire: Victims of Gang Violence.” Photo: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times

It was foreign enough to me, and I said, “Wait a minute, this is really wrong.” I spoke to my editors, and we agreed that I would do a comprehensive visual investigation on the consequences of this long-term effect of gang violence right here in Los Angeles.

One of the stories told in Caught in the Crossfire really stuck with me – the story of Rose Smith, who was shot when she was pregnant. Can you tell us what happened?

Rose Smith was the first person I met. She was the impetus for me to take this assignment. I thought that if nobody’s interested in her story, how many other people’s stories have not been told?

Rose was an innocent civilian. She was coming home from grocery shopping. It was the holiday weekend, Memorial day, and she was getting out of the car. She had her groceries, and the kids – the two- and three-year-olds at the time – were banging on the window to say hi to their mom.

“Caught in the Crossfire: Victims of Gang Violence.” Photo: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times

And all of a sudden, shots rang out. Two gangs were feuding, they started shooting, and she got hit. She got hit in her jaw and her spine. She was hit four times and fell to the ground, and she’s never walked since. She has been paralyzed from the waist down. The bullet missed her child in the blink of an eye. I met her daughter, who was in her mother’s womb when she got shot, 15 years later. Her name is Miracle.

If nobody’s interested in her story, how many other people’s stories have not been told?

This project really changed the way I operate as a photojournalist. I did such a deep dive on that story that it became a commitment. And some of the people I photographed became close friends.

I know there’s this mantra that you have to keep an emotional distance from the people you’re photographing, but I think when you’re telling a story that’s this intense and impactful, you do become emotionally invested. And I think that that’s part of the process of telling a powerful story because we’re not robots. We can’t just turn that off.

Seeing all that violence across the globe and in the very city you live in, how do you cope with all the emotional toll this kind of job takes on you?

I would be lying to you if I said it didn’t take a toll on me. Repeatedly being exposed to trauma has a secondhand effect, and taking care of one’s mental health is very important.

Afghanistan. Photo: Courtesy of the Dallas Morning News

Early on in my career, I didn’t really understand any of that; I just kept on going, and going, and going. And then I started reaching a point where I wasn’t behaving like myself.

This is usually the first sign that something is not right with your mental state.

Right. I would cry more or get angry really easily.

I don’t talk about this a lot, but I was actually held captive at the end of the Bosnian war. I, myself and my Croatian driver were in the wrong place at the wrong time, and the Arkan, a very dangerous paramilitary outlet, took us for 48 hours. It wasn’t very long, but when you don’t know if you’re gonna live or die every second of that 48 hours, it’s very traumatic.

With the trauma of covering the trauma, it has definitely taken a toll on me. I’ve been diagnosed with PTSD, but I take care of my mental health. It’s a priority.

Given everything you have been through as a photojournalist..was it worth it?

Nobody has ever asked me that. I’ve devoted so much of my life to covering that I think my work is a calling, and it goes way beyond a 9-5 mentality. And when I say it’s a calling, I don’t say that lightly. I feel like I was meant to do this.

I feel like a visual humanitarian, I feel like my work is meant to educate people about what is happening in the corners of the world that they might not know about – whether it be in my own backyard in Los Angeles, or Afghanistan, or Gaza. For me, it’s all the same – it’s about telling stories of marginalized communities.

Sri Lanka Tsunami. Photo: Courtesy of The Dallas Morning News

And when you ask me if it’s worth it, I look back at all the incredible adventures I’ve had, and I would never switch out of that.

I feel like I was meant to do this. I feel like a visual humanitarian.

I’m so grateful for all the experiences that I’ve had. I’ve had an incredible adventure, but I’ve also paid the price for that because you lose a little bit of your soul every time you tell a story that is painful. I don’t get attached to every single story I tell; I keep a distance and emotional distance.

You need to protect yourself.

I need to protect myself because, in many ways, if I’m incapable of composing myself in the moment, I don’t get the pictures. And if I don’t get the pictures, I’m doing an injustice to the people I’m documenting. So you have to remain composed. But I’m not gonna lie to you – it has taken a huge toll. It is the price you pay, you lose a part of your soul, but the rewards far outweigh the negatives.

Deep dive, a “heavy” kind of storytelling, is more difficult for people to want to engage with because it hurts.

In the era of social media and entertaining content, do you feel like the work that you do and the stories you cover get as much appreciation as this kind of work truly deserves?

Things like live videos on TikTok are a sort of escapism.

I devour TikTok and Reels and social media myself. It’s right there on our phone. It’s easy to access escapism. And most of us get sucked into that. It’s our reality. Deep dive, a “heavy” kind of storytelling, is more difficult for people to want to engage with because it hurts.

Navajo Nation, Arizona. Photo: Courtesy of the Los Angeles Times

And I understand that, but we can’t become a society of only caring about sugar and spice. We need to be mindful of what we engage in, thoughtful and cause-orientated as a society.

It’s not as easy to get access to the harder-hitting stories, but it’s important for media outlets and social media outlets to still deliver these stories because they really matter.

Speaking of a technical site for taking a photograph, how do you “see” a story, and how do you capture that through the length of a camera?

This process involves a lot of journalism, apart from visual journalism.

When you see something, you ask yourself, “Does this make a good visual story? Is it a good word story as well? And when you can marry those two, it really elevates the game of that story. But that doesn’t happen every time. To find that beauty, that sweet spot, takes a lot of time to figure it out.

Afghanistan. Photo: Courtesy of the Dallas Morning News

This is what happened with the gang violence story. That’s the reason it became so successful – because the journalism was so powerful.

What is the most important photo you feel that you have taken?

This might be one of the toughest questions to answer. I do have photos that touch me more than others. Some of the photos are more historic, like covering the presidency. But there was a moment that got to me early on in my career in Ukraine.

Ukraine was my first overseas story, and there was a little boy in a cancer ward. He had gotten sick from Chernobyl. When you asked me that question, the picture of that little boy popped into my head because I remember seeing his little body and all these spots from the medicine their doctors put on him.

I have an emotional connection to so many of my photographs, but there are images that hold onto my heart longer than others, for sure.

Do you do other kinds of photography?

One of the reasons why I left my job is because I wanted to create all kinds of things and avenues. After I left the Los Angeles Times, I did a big campaign for Volvo.

I used the safety system in one of the brand’s cars to take images, and that was phenomenal. I mean, that challenged me in every aspect of my creative process. I was the director and the videographer, and I curated the show.

The work that we did was all shot on a video safety camera. I then went through the video and pulled stills for the exhibition. That was such a creative highlight for me.

As for the rest of it, this old 8X10 camera that I’m using is unique. I love going into the desert and making beautiful portraits of trees. I have a vast, vast array of things I like to photograph; it’s not all violence. And I think that’s what helps balance me psychologically because I spend a lot of time making pretty pictures.

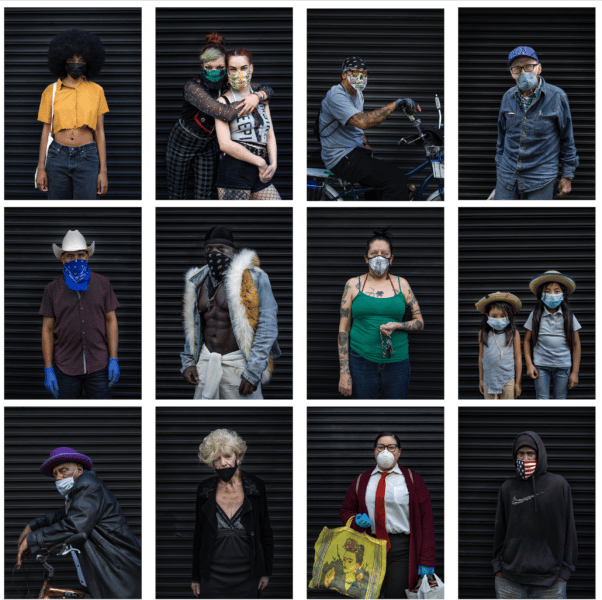

Photo: Courtesy of Barbara Davidson

How do NFTs fit in your story?

I am always open to new creative endeavors. I’m not just a photojournalist, I’m a photographer who dives deep into all kinds of creative avenues. That’s who I am, and that’s what I do.

I felt that I was diving into a new tribe of creativity, inspiration, and lightness.

A while back, my good friend Scott Strazzante convinced me to look into non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which I hadn’t heard anything about before. And I started looking into it.

I went through OpenSea, navigating to understand how it works. While you’re doing it, you’re faced with this really complex system just to get on the platform. It was really daunting, but I stuck to it. I asked Scott and my other friends for help and finally got my collection launched.

Barbara’s first NFT collection depicted the pandemic in Los Angeles

The NFT space is such a wonderful new avenue of excitement and creativity; it feels like a community. I fell in love with it because the photojournalism community, as much as I adore all of us, can get a little dark at times, whereas with NFTs, everybody’s really excited and friendly and creative. Everybody’s patting one another on the back. I felt that I was diving into a new tribe of creativity, inspiration, and lightness.

And from the financial perspective, did you manage to make money through OpenSea?

I did make some money from OpenSea. And then the market crashed, so I don’t have that much anymore.

I then decided that instead of launching another series of images, which everybody does, I wanted to better understand the culture, to know who the players are and what kind of work was inspiring.

So I’ve really been at the beginning of a lot of new initiatives in the space, but it’s time for me to launch another collection.

With NFTs, there has been a lot more attention to art. There is a common belief that this space has allowed artists to earn more and be recognized for their work. So what kind of future do you envision for NFTs in the creative industry?

NFTs definitely create a beautiful income stream for artists.

We cannot underestimate that the gatekeepers in the real world sometimes stifle the advancement of photographers, and the NFT space really eliminates that; those gatekeepers are melting away, and it empowers the photographer. It gives them agency over their work. And if they’re smart about promoting their work in the space, they’re gonna do well.

You are an advisor to Amberfi. How did you learn about the project, and what does your role entail?

Amberfi happened because I’m one of the seasoned photographers in the space who is really vocal and a part of a community that really wants to see the culture grow.

I’m part of the culture that is working to raise awareness within the photography community to help ease people into the space, and I’m doing that in partnership with Amberfi, which is a marketplace that’s making it easy for people to enter the space.

I see my role as an ambassador to help make it as seamless as possible and help the product be very easy to use so that photographers don’t get frustrated with the technical aspect. Because when they do, they shut down. I’m just helping to make sure that the experience is seamless.

Cover image: Courtesy of The Dallas Morning News